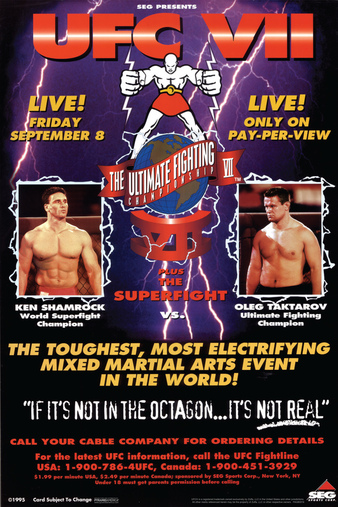

In the 90s, particularly in the early to mid 90s, Japan was still shedding its roots in professional wrestling. This means organizations like Shooto, RINGS, and Pancrase were focused on building STARS. The only thing more important than building stars, was making these stars bigger and bigger. In 1995, Pancrase was home to a few big names. Masakatsu Funaki and Minoru Suzuki were the obvious ones (as they founded the company), but more fighters would bring the Japanese promotion to success, including foreigners. We’re talking about guys like Ken Shamrock, Bas Rutten, Frank Shamrock, and Guy Mezger. Ken was leading the charge when it came to American stars in Japan, given that he had been competing there as a professional wrestler since 1990. By 1995 he had amassed a 15-3 record in NHB and beaten virtually everyone in Pancrase barring Suzuki, who would essentially become his Dennis Hallman. A catch wrestler who had become competent enough as a striker, Ken was as skilled and as tough as they come, and one of the absolute best fighters on the planet during that time. He was the first foreign fighter to become the King of Pancrase (or champion of any Japanese organization), a title and accomplishment endeared and respected by all. And here comes one of the biggest legitimate squash matches I’ve ever seen in MMA and NHB.

The World’s Most Painful Submission

In January of 1995, Pancrase found a lamb and slapped it on a platter for Shamrock to feast on. He was a training partner of Bas Rutten, who Ken had two wins over, and was coming into this matchup as an 0-1 professional, with his sole fight being a loss to Vernon White by heel hook. Now Vernon White was a good fighter who was probably closer to being a natural middleweight, and he was fighting guys much bigger than him, who (almost) all had a grappling or wrestling background. He also churned out some solid wins in his career, including a later win over Dave Terrell. All this to say that while White was a pretty good fighter at the time, if you’re losing to him on the ground by heel hook, you’re probably not ready for The World’s Most Dangerous Man. There was nothing to suggest that the fight between Ken Shamrock and Leon Van Dijk should have been made, other than they needed to make a fight and it needed to make their star look good, so it was made, and boy did Ken Shamrock look good.

Bas Rutten has since described Leon as his “main training partner” in the 90s and has also alluded to Leon being an utra-tough and violent guy, presenting him as a loose cannon who got into many fights on the streets of Holland. All of that aside, Leon comes from a Dutch kickboxing background, which he displayed well against Vernon, pressuring him and forcing him to look for a takedown. On the ground he displayed rudimentary defense, something that would be eaten alive by Ken Shamrock, ultimately fleecing Leon. Heel hook was a specialty of Shamrock and he would need some strong deodorant, taking the feet of many poor souls and twisting them into oblivion. The contest would last less than five minutes. When the action started, Leon opened with a low kick, to which Ken countered brilliantly with a PIVOT-SIDESTEP-LEFT HOOK. UFC FIGHTERS, ARE YOU TAKING NOTES? Shamrock easily takes Van Dijk down. From here it’s clear Leon has done his homework: He’s clasping his hands together to prevent an armlock, something we saw him do against Vernon White. While Shamrock is distracted trying to break that grip, Leon would either pull Ken’s head down close his own chest, or sweep one of Ken’s legs to stop him from standing up (which Ken needs to do in order to roll for a leg lock). Despite this, Ken gets ahold of Leon’s left leg anyways, but gets overzealous and doesn’t control Leon’s hips. Van Dijk uses this to his advantage and briefly gets top position, which Ken reverses. After narrowly escaping a kneebar with a rope escape, a tired Van Dijk is taken down again, and this process is repeated again and again as Van Dijk gradually gets worn down by the grinding pressure of Shamrock, until Ken easily steps over into full mount. Shamrock gets ahold of Leon’s left leg again and rolls into a heel hook, turning his foot and squeezing with his left arm to hold it in place. The silence of the crowd is broken with a verbal tap of “AHHHH! AHHHHH! AH SHIT!” coming from Van Dijk, his desperate cries met with concern from the ring officials. Leon Van Dijk was in serious pain. With almost no strikes landed and most of his time spent being dominated on the ground, four minutes and forty-five seconds proved Leon Van Dijk had nothing for Ken Shamrock, and suffered a broken ankle for his troubles. It was clear this fight shouldn’t have happened to begin with. In a 2015 interview, Ken talked a bit about the heel hook, saying he didn’t purposely use unnecessary force:

“The reason why that one happened was because when I put that on, it was cross-body, and he laid backwards. And when he laid backwards it had put more pressure on his heel, and I was sitting up and I went backwards- and it was just one of those things that happened. I would never try to hurt anybody on purpose, especially at the level that he was at. Like I told you, I even talked to Leon Dijk and Bas Rutten before that, and I made it really clear- I’m not gonna go in and beat this guy up- he’s a young kid, he doesn’t know anything- and so that was not my intention.”

Fights like this one eventually led to Pancrase banning heel hooks, which led to fighters using ankle locks and other hold modifications to “toe-tag” their opponents and make them tap (or hurt them). I will acknowledge that getting thrown to the wolves thirty years ago is a lot different from being a sacrificial lamb now. Back then, there weren’t a ton of fighters on the professional circuit, and making fights between two closely matched guys could be extraordinarily difficult, and sometimes nearly impossible. Nowadays it’s much easier to fill up a card, as generally there are lots of fighters on the regionals waiting for their big shot, guys in between fights who need to make more money, or just want to take a fight because they are getting ancy. In the 90s there was a general sense of toughness and desperation, with a lot of men becoming professional fighters out of pure necessity, or because fighting was the only path that stood between jail and death. Were there better or more competitive matchups available for Ken that night? Sure. Of the Pancrase roster, Shamrock never fought Jason DeLucia, who had wins over both Suzuki and Funaki, and Shamrock was never matched up with Vernon White, a longtime Pancrase veteran. Regardless, Leon Van Dijk became another victim of the Ken Shamrock heel hook that night.

Don’t Let The Dog Out Of The Kennel

By 2005, we’d seen almost everything. We saw Kevin Randleman knock out Mirko Cro Cop and then Cro Cop submit Randleman with a guillotine, in a surrealist picture that only Japanese MMA could paint. We saw football-player-turned-unskilled-real-life-Blanka Bob Sapp knockout one of the best heavyweight kickboxers, Ernesto Hoost, TWICE. We had seen the rise of fighters like Wanderlei Silva, Fedor Emelianenko, and Kazushi Sakuraba – the latter of which this next fighter has a win over. His name is Kiyoshi Tamura. Kiyoshi was a professional wrestler-turned-fighter, who’s MMA career was born out of the desire to test himself in an actual fist fight. Following the demise of Universal Wrestling Federation (UWF) in 1990, Tamura turned to its successor, Union of Wrestling Forces International (UWFi). In 1992 he trained under Lou Thesz, who sharpened his wrestling skills, and helped him become the best wrestler in UWFi. After participating in two shootfights (real fights), the wheels started turning and by 1995, he was unsatisfied with the direction of professional wrestling, wanting to participate in real contests, not predetermined works. After negotiations with Pancrase and RINGS, Kiyoshi Tamura made his RINGS debut in 1996. He would collect a record of 26-11-3 by 2005 and defeat the likes of Maurice Smith, Pat Smith, Dave Menne, Pat Miletich, Renzo Gracie, Jeremy Horn, and Valentijn Overeem. He even fought to a draw with Frank Shamrock (who was in the middle of a massive win streak). Tamura was the former 2x RINGS Openweight Champion. These aren’t the wins of a bad or even decent fighter, this a resume far beyond that of your average Japanese jobber. Although so far Tamura hadn’t had the best luck in PRIDE, having been matched up against Wanderlei Silva and Bob Sapp in his first two fights.

At PRIDE 29, Kiyoshi Tamura met a man named Aliev Makhmud. Let me just preface this by saying we don’t know much about Makhmud. What we do know about him is that he is a multiple time Azerbaijan Freestyle Wrestling Champion, and became the face of wrestling in the Eastern European country for a period of time in the mid 2000s. We can assume PRIDE promised him a lot of money for a last minute fight against Kiyoshi Tamura, and aside from that, Makhmud is an enigma. The fact that Aliev was NOT a professional fighter and had never fought before makes this one of the worst squash matches in MMA history (and worse than Tamura having to fight Wanderlei Silva in his PRIDE debut, but that’s another story). Aliev Makhmud is introduced as 5’7’’, 187 pounds. He is 35 years old, and conveniently described as “making his debut in PRIDE Fighting Championships”…. And yet, during fighter announcements, Aliev appears remarkably calm for somebody in a ring for the first time in front of over 22,000 fans, almost like he thinks this is a huge wrestling match (and is wearing wrestling-style shorts). Makhmud comes out in a square stance, hands down, feinting and jumping at Tamura from 8 feet away without coming close to touching him, like a 6 year old boy who just got let out of a dog kennel. Aliev bullrushes Tamura and gets him up against the ropes, landing two decent short punches, which may have been the most significant thing he did the entire fight. Once they are separated Makhmud lunges in again, and eats a nice punching combination from Tamura. I will say that I was impressed with at Makhmud’s reaction to taking punches, he didn’t seem to mind them all that much, and it didn’t stop him from trying to close the distance and wrestle. Once the bulldog calmed down, Tamura walked into range and slammed him with a middle round kick or low kick, watching and waiting for more unusual tactics from Aliev.

At one point Makhmud does get a takedown but is unable to do much with it, Tamura stands up, and Makhmud gets a double collar tie. He pulls Tamura’s head down and it appears as though he is landing knees, but in reality, he is landing with his mid-thigh, which is not a damaging technique. Tamura blocks them with his forearm, and waits for him to finish throwing. At this point Makhmud is starting to look tired, their separation met with deep breaths and stationary legs. The two throw flying knees at the same time, with Kiyoshi’s knee incidentally pulverizing Aliev’s nut sack. After recovering from the low blow for three plus minutes, Bas declared that Aliev Makhmud was “quitting”.

After five minutes of rest, Aliev in fact did not quit, and the fight resumed. Makhmud then attempted a leaping side kick that would leave Karate practitioners gasping for air, jumping with a forty inch vertical, and somehow eating a mid-air low kick. Makhmud ate another kick and kept coming, froggied his way back into range and cracked Tamura with a left hand. Tamura was surprised by this, ate another right hand, and backed away. A follow up flurry by Aliev would yield no damage, as Tamura would land a lead hook counter and move away. With about six minutes remaining in the first round, the two exchange glares while engaging in a lengthy staring contest. Makhmud, without the IQ or skills of a fighter, has been jumping around for four minutes, and is now exhausted from the parkour. He backs up into the ropes and Tamura knows something is up, and while Makhmud is signaling something to the ref, Tamura lunges in and lands two body kicks. This is followed by a “just kidding” moment when Aliev blitzes Kiyosha, misses on a punch and whiffs badly on a leaping, spinning back kick attempt that would make even 1960s Kung-Fu movie choreographers wince. Tamura knew it was only a matter of time so he just kept stalking, landing a jab followed by another middle kick.

Aliev Makhmud is now talking to the ref and Tamura, but it’s unclear what he’s saying, or what language he’s speaking. He grabs the ropes and squats down, grabbing his groin, with all signs pointing to his resignation. Aliev shakes his head and waves to the ref, and the fight is called.

Putting aside the fact that this was a huge mismatch, confusion throughout the round at Aliev’s unusual behavior may have actually prevented the referee from stopping the fight earlier, as he may have thought this was part of Makhmud’s game or strategy. After the fight was stopped, Tamura left the ring immediately, completely bamboozled at the lack of honor and frog-like tactics of Aliev. Mauro Renallo sums up the bout as “a page out of the Pride Fighting Championships twilight zone”, and refers to Makhmud’s unusual movement as “yo-yo mannerisms”. On the other hand Bas is left speechless, merely recommending that Makhmud “work on his stand up” before he takes another fight. Either way all Kiyoshi Tamura had to do was move out of the way for most of the fight, land some jabs and a few counters, and let Makhmud walk into liver kicks repeatedly. The result of the fight reflected the matchmaking, and Aliev Makhmud proved that to be a fighter, you have to actually be a fighter.

The Best Versus The Guest

PRIDE Fighting Championships did some crazy shit, and their audience were no strangers to seeing their favorite Japanese wrestler get knocked out by a budding star that the promotion was looking to build. While this was reserved for future standouts and current superstars, PRIDE was actively engaged in a more subtle form of fight-fixing: keeping their most popular fighters popular by matching them up against less popular fighters who weren’t good fighters, who would never be good or popular fighters (or were has-beens). One such example of this is one of the most one-sided, if not THE most one-sided fights I have ever seen. Indubitably this would be Fedor Emelianenko vs. Wagner da Conceicao Martins, or as we will refer to him, “Zuluzinho”. A lot of people have knowledge of this fight. But if you really look back on where Fedor was in his career, the run he was on, who he beat, and the little we knew about Zulu, you’ll come to the same conclusion as me – this was freight train versus model train. This fight took place at PRIDE Shockwave 2005, on New Year’s eve, less than a year before PRIDE went defunct. Without knowing this fight existed, we can look at those two names and see a discrepancy. One is recognized as one of the greatest MMA fighters to ever live, and the other is an obscure Brazilian name that only the most hardcore fans of MMA would know. By this time Fedor was 11-0 in PRIDE, the PRIDE Heavyweight Champion with two title defenses, and had semi-recently won the PRIDE Heavyweight Grand Prix, and defended his belt against Mirko Cro Cop. On the other hand, Zulu was coming off a win over Henry Miller (???), which was his only fight in PRIDE. With all of his fights together, he was just 5-0, with all of his wins coming over unknown or virtually unknown opponents. I couldn’t find any of his fight footage on YouTube, but based on his win over Henry Miller (???), it’s likely his other fights went the same way, based on my perception of what low quality opponents they could find for him in the Brazilian regionals. Being that the man is 6’ 7’’, 341 pounds at the time of the fight, he had a full 7 inch, and 100 pound size advantage. Size doesn’t matter when your opponent is the pound-for-pound best fighter in the world.

After watching his brother Aleksander submit debuting fighter Pawel Nastula, Fedor was ready to walk to the ring. There was no reference to the gigantic mismatch anywhere in PRIDE promotional material – only a comment about a potential “shockwave” sent to the MMA community if Zulu were to win, which was given a response of “that’s not gonna happen, Fedor is going to dispatch this man very quickly” by PRIDE commentator (and fighter) Frank Trigg. Both men move to the center of the ring and Fedor starts with a series of hip feints, Fedor hits Zulu with a right hand that hits his chest, and uncorks an unearthly left hook that drops him, covering an incredible amount of distance. After a few follow up punches and a soccer kick to the ribs, Zulu is able to stand up. But before he can completely do that, Fedor is already loading up, and smashes into him with a flying right hand, like he’s playing a violent game of whack-a-mole. Zulu crashes to the floor again, his momentum only stopped by the canvas below, shaking and fluttering under his weight. Fedor tosses his legs aside like a bone he just licked clean, and finishes him off like a ravenous beast, lacerating his pounding flesh until Zulu yields to Fedor’s superiority.

This 22 second video is the entire fight. Surprisingly, Zuluzinho’s dad is a legend in Brazil, whose name is Casimiro de Nascimento Martins, and is known as Rei Zulu. Rei was born in 1947 and in contrast to his overblown son, Rei had more of a chiseled physique. According to Brazilian legend, Zulu travelled around Brazil looking for fights. He is alleged to have had over 100 Vale Tudo fights, training in a style called “tarraca”, a northeastern Brazil form of folk wrestling. If you look at his record he is officially 2-7 in combat sports, showing his debut to be against Rickson Gracie in 1980. By this time he was already 33, and had fought dozens of times before (allegedly). Rickson submitted him twice and Zulu even fought Ebenezer Fontes Braga and Enson Inoue in the 1990s, when he was in his 50s.

For his son Zuluzinho, he wouldn’t become as notable, and his MMA record currently sits at 14-12, with his last fight being a loss in 2022. After his loss to Fedor he would go on to become winless in the remainder of his PRIDE run, falling to Big Nog (give the guy a break), and Butterbean. You could argue he wasn’t given a fair chance in PRIDE, being thrown in against Fedor, and then another one of the greatest heavyweights in history, Nogueira. It’s kind of nuts when you think about it but they did give him Butterbean, which was a much better matchup for him, and a fight he could have won if he was to be in the big show. That didn’t pan out and it just goes to show how many levels there are in fighting, and why some fights just shouldn’t be made.