Return To The UFC

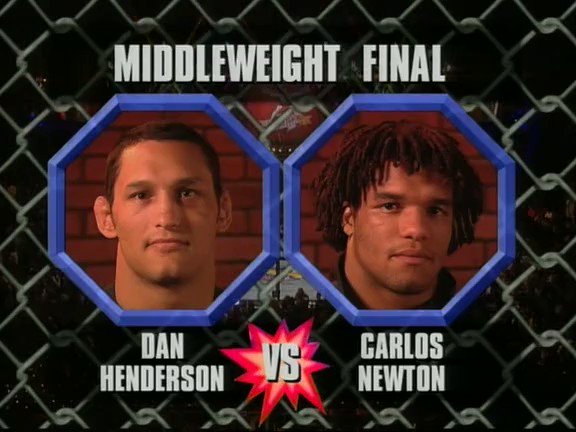

After Vitor Belfort’s absolute annihilation of Matt Lindland in January of 2009, we would never see him compete outside of the UFC again. For the last four years, Belfort fought in PRIDE, Strikeforce, and even won a world title in Cage Rage – not having competed in the UFC since he faced Tito Ortiz at UFC 51 in February of 2005. That didn’t seem to matter to Belfort, as he appeared as confident and excited as ever. He was fighting Rich Franklin – a former champion and beloved fan favorite. Rich was a few years removed from his championship run at middleweight, but his age and experience would deceive you at first glance. At that point the only losses he had in his ten-plus year career were Lyoto Machida (former champion), Anderson Silva (we all know), and Dan Henderson (former PRIDE and Strikeforce champion). Even then a lot of people (including myself) thought Franklin beat Hendo. Given that Belfort was looking better than he ever had before, this was a big test to see if he would be a contender in the UFC, and for Rich, it was a big test in seeing if he could rise back up the ranks and make another title run. Although Franklin had a long run by then, these two were still close in age and tenure, with Belfort being 32, and Rich being 34. The matchup took place as the main event of UFC 103, which was originally supposed to be Rich Franklin vs. Dan Henderson II, but fans convinced the UFC that they didn’t want to see a rematch of the fight they just saw earlier that year. The two fighters (Vitor and Rich) agreed this bout would be at a catchweight of 195 pounds, as both of them competed at both 205 and 185, feeling their best in between. I remember when this fight was announced I was excited, but being a fan of both guys, I didn’t want to see either of them lose. But I knew if Franklin won it would spoil Belfort’s title hopes, and being that Rich was already the champion, I wanted to see Vitor get that chance. Plus, I REALLY saw Belfort as a huge threat to Anderson Silva (hehe), and I wanted to see that fight badly.

Event: UFC 103 | September 19, 2009

Record Before Fight: 18-8

Opponent: Rich Franklin

Opponent’s Ranking: 7 (Light Heavyweight – 205 lbs)

Result: Win // KO (Punches)

Score: 4 points

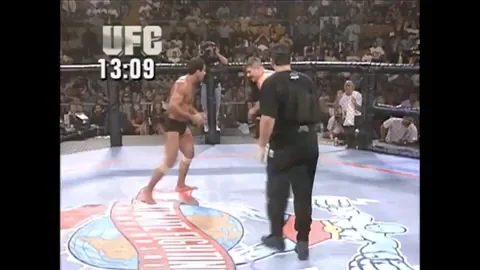

I will say that in this fight, Rich Franklin looked uncharacteristically nervous. That’s not to say he’d never had nerves before but you can tell during the glove touch and when the opening bell rings, that Rich is a little off. Once they start feeling each other out it becomes clear that Rich is being cautious because of Vitor’s power, at a few points even becoming noncommittal in his strikes. Two and a half minutes in, Rich whiffs on a right hook and Vitor shows his right, and sort of paws it out there. This causes Franklin to pull back right away. Rich then throws an overhand left, which Vitor easily avoids, and Rich retracts quickly, wary of the counter. Belfort, looking as calm as ever, begins to stalk his prey. They both jab at the same time but Belfort ducks under the one aimed at his head, and lands his own. In the same motion he follows up with a rear uppercut and right hook, both of which graze Franklin’s chin. Vitor feels he is getting close and in an instant, he throws another jab and a left overhand/hook hybrid punch. The angle starts on a downward slope like an overhand, then he swings it around in a circular motion, finishing the technique like a wide hook. What’s crazy about this punch is that it seems to barely graze the back of Franklin’s right temple, towards the back of his head, sort of in the spot where you would let your over-ear headphones rest momentarily if you took them off your ears. When the punch landed Franklin was looking for a lead hook of his own, but barely engaged his shoulder. Vitor Belfort knocks out Rich Franklin in the first round, three minutes in. To me the speed advantage for Belfort was stark, and much more evident than I would have ever imagined. I knew that Vitor had super fast hands and Rich was never known to be particularly fast or explosive, but still, the difference was staggering.

The Spider’s web

Let’s go over a bit of timeline here. Since April 2007, Vitor has put together a 5 fight win streak, with wins over Serati, James Zikic, Martin, Lindland, and now Franklin. The Cage Rage fights notwithstanding, and particularly the last two wins, make it a good run, with definitive results in each. After Belfort knocked out Rich Franklin, I really felt like he was the man to get the job done against Anderson Silva. At the time I strongly disliked Anderson for beating all of the guys I was a fan of (as is the case with most champions who beat all of my favorite fighters), and making them look stupid. But, everything I saw in Belfort’s fights made me believe he would be the one to give Anderson a true challenge. Considering Belfort was a Brazilian Jiu Jitsu black belt, I wasn’t worried about him on the ground, especially given that he had much improved wrestling and top game, something well known to be a weakness of Silva’s. Belfort’s striking looked as good as it ever had, and he had developed a sniper-like style, where he calmly pressured his opponents, avoided whatever they threw, got their timing, and landed whatever shots he wanted. By this point in his career Vitor was known for his vicious countering almost as well as he was known for his blitzing during his early career, and it really made guys freeze in there, not knowing what would be coming back their way if they were aggressive against him. On top of that he matched up well against Anderson stylistically, bringing a more straightforward, pressure-based boxing approach, versus Anderson’s more Muay-Thai-meets-Traditional-Martial-Arts style, which in my head worked to Belfort’s advantage, and it helped that I was still in denial about the pure skill level of The Spider. After Belfort’s win over Rich, he finally faced Anderson Silva at UFC 126 in February of 2011. He was a slight underdog and was seen by a lot of fans as the striking equivalent of Sonnen, not in the sense that he would dominate, but that he would really push Anderson. Well that didn’t happen. Three minutes into the fight and really before a single exchange, Anderson front kicked Belfort in the chin, creating not just one of the most unique knockouts in the UFC, but one of the most legendary and iconic moments in the history of MMA. This was obviously a brutal setback for Belfort, and he had his sights set on becoming the UFC MIddleweight Champion, but the sorrow didn’t last long, as he returned six months later against Yoshihiro Akiyama and provided fans another first round knockout. This was followed by a win over a blown up Anthony Johnson, another first round finish. Vitor Belfort was scheduled to fight Alan Belcher at UFC 153 in October of 2012 and he was training for that fight when he got a call from the UFC brass, asking if he could step in at UFC 152, a month earlier then his scheduled matchup, to fill in for Lyoto Machida in a championship fight. That fight was against none other than Jon Jones, at 205 pounds, and Belfort accepted. After putting Jones in the most trouble he had been in with an armbar in the first round, Jon largely dominated Belfort for the remainder of the fight, taking him down and punishing him, and eventually finishing him with a kimura in the fourth round.

Elephant In The Room

Now here’s where shit gets weird. I’m not going to go into complete details about this but I feel anyone who has been a fan of the sport for at least 15 years will know exactly what I mean when I say “the elephant in the room”. When it comes to Vitor Belfort, this elephant is fully grown, and isn’t going anywhere until we address it. Over the years this phrase has turned into a way to define his career, completely dwarfing (and ultimately adding onto) the existing framing of his fight story. In September of 2012, a few weeks before Vitor stepped in to face Jones, the UFC accidentally sent out an email to a group of UFC affiliates (fighters, managers, and others) containing the results of Vitor Belfort’s most recent blood test results. Huge mistake, right? Despite their best efforts to mitigate this error and pretend like it didn’t happen, it still happened, and soon this document spread like wildfire, revealing the elevated testosterone levels inside of Belfort’s blood. If you want to read more about this, there’s a good article from Deadspin here. Five months after his loss to Jon Jones, it was made known that Vitor Belfort received a TUE for the fight, which stands for Therapeutic Use Exemption. This meant that due to low testosterone levels, Vitor was allowed to take synthetic testosterone (TRT) to bring his body back within a “normal” range of production. From an ethical standpoint, Belfort shouldn’t have been allowed to fight Jones, yet three weeks after this blood test, he was competing for a world title. With the Jones fight behind him, escaping the questions and controversy surrounding his TRT use, Belfort went to Brazil and knocked out his next three opponents, all in Brazil, all while using TRT approved by the Brazilian Commission. Vitor Belfort wasn’t the only fighter who received TUE’s or used TRT legally, but he was the most criticized for it, and I believe it’s because of the way he outright annihilated Michael Bisping, Luke Rockhold and Dan Henderson, securing himself a title shot against Chris Weidman at middleweight (who HATED that Belfort got the shot). Do I believe that Vitor Belfort was using a legal system to abuse TRT, in order to gain an unfair advantage? I do, but that’s not what this article is about. Don’t worry Vitor, I’m still a big fan. As for you, the person reading this, you can make that decision for yourself.

Don’t Look Back

Let’s get back to why we’re here. With the Jones fight in his rearview mirror, Belfort sought redemption at what he felt was his optimal weight class, middleweight. Never one to revel in a loss or agony, Vitor turned around to face number 7 ranked Michael Bisping. Belfort went in with a renewed vigor and confidence, looking to pick up where he left off against Akiyama and Rumble. Believe it or not the odds were close to dead even in this matchup. It seems surprising at first given Belfort’s resume and Bisping’s tendency to be underrated, but with Vitor coming off a loss where he was dominated, and Bisping having been on quite the run with the exception of his loss to Sonnen, it was enough to even the score between the two of them.

Event: UFC on FX 7 | January 19, 2013

Record Before Fight: 21-10

Opponent: Michael Bisping

Opponent’s Ranking: 7 (Middleweight – 185 lbs)

Result: Win // KO (Head kick and punches)

Score: 4 points

The first few minutes of this fight didn’t see a lot of action, with Bisping controlling the pace, landing some low kicks and a few good jabs. About two minutes in, we see Belfort trying to time Bisping’s jab with a 1-2 of his own, missing on his left cross the first few times. Bisping notices this and starts using his right hand more, and Belfort responds. He slips a right hand and simultaneously gets a collar tie with his lead hand, blasting Bisping with a rear uppercut. Bisping starts feinting the jab and gets back to the low kicks, and Belfort responds with a few rear middle kicks, followed by an overhand left. In the closing seconds of the round Belfort feints the overhand left, gets Bisping to duck, and slams in a high kick. This wobbles Bisping but doesn’t come close to finishing him, as Belfort stalks him for several seconds. That round was more tactical than I remembered, with both fighters making adjustments multiple times. Close round but the final seconds probably gives it to Vitor. Bisping opens the second with more low kicks, as Vitor is still looking for his hands, but landing some body kicks. Less than two minutes into the round Vitor lands a rear high kick that puts Bisping down, and he finishes the job. There were two different setups for that high kick for those paying attention. In the first round it was the overhand left (accentuating the feint by lowering his hips and shoulder just enough). In the second round it was landing the middle (body) kick that Bisping didn’t seem to have an answer for. Belfort feinted to the body and went to the head. Another knockout finish.

The Streak Continues

After head kicking Bisping, Belfort was ready for his next challenge. In January of 2013, then Zuffa-led Strikeforce, announced that “Strikeforce: Marquardt vs. Saffiedine” would be their final event, and decisions would soon be made on which fighters would be coming over to the UFC. One such fighter was Luke Rockhold, which was a no-brainer, because he was the reigning Strikeforce Middleweight Champion, ready to come into the UFC and beat whoever he needed to, keeping his Strikeforce belt warm while in pursuit of his own UFC gold. Leading up to the fight Luke said he wanted to “give Vitor his respect”, acknowledging that he has gotten sloppy in the past due to his overconfidence against other strikers. He even alluded to using his roots to potentially taking Vitor down and beating him there. When asked about Vitor’s TRT usage, Luke took a stance against it, but during fight week, he moved forward, assuring the media that all he cared about was the fight, and wasn’t thinking about Vitor’s testosterone levels. When Belfort himself was asked about it in the pre-fight presser, he said he was doing everything legally, and that “TRT doesn’t win fights”. Vitor adds that not only does it not win fights, but that a lot of people that are using, are losing (teehee). Which was true, at the time he was one of only two fighters who hadn’t lost since starting TRT usage. Either way Belfort saw Rockhold as a stepping stone to another title shot, and treated him as such in their fight. When this fight happened it was a big deal because Strikeforce (like PRIDE) was seen as having some of the best fighters in the world, along with the UFC. Not only was this a way to test that theory, it was also an exciting debut for a fighter who was on a 9 fight winning streak, against the most dangerous version of a UFC veteran who had fought for a title multiple times before. The odds for this fight were about even going in, reflecting the respect the oddsmakers had for Rockhold and his “legitsu”.

Event: UFC on FX 8 | May 18, 2013

Record Before Fight: 22-10

Opponent: Luke Rockhold

Opponent’s Ranking: 5 (Middleweight – 185 lbs)

Result: Win // KO (Spinning heel kick and punches)

Score: 6 points

No glove touch accompanied by a roaring crowd got this one started. The first minute sees a lot of moving around, and an uncharacteristic, diving shot from Luke Rockhold. In my eyes this gave Belfort confidence not just from defending the shot itself, but from the fact that Rockhold even shot it at all. This action makes Luke’s intentions clear: Take Vitor down and pound on his face. Rockhold did a good job of leading with his right side kicks, and Vitor showed hands when Luke decided to close the distance instead. Rockhold never being one to back down from a fight, he continued peppering Belfort’s lead leg, and held strong in the center. Less than three minutes in, Belfort landed a spinning heel kick, with the crowd being the only thing louder than his thunderous follow up shots. You can see Luke bring up his rear hand and as the kick lands, almost had his lead hand over for a double block. Based on his reaction it seemed like he thought it was going to the body but instead went to the head, and BANG.

What goes up, must come down

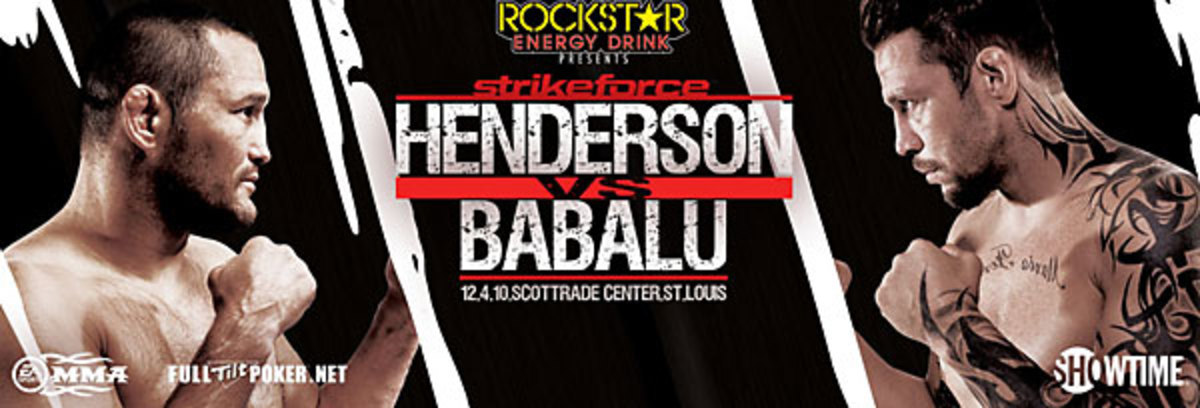

The Dan Henderson that Vitor Belfort fought at PRIDE 32 was not quite the Hendo of legend that developed over the following decade and yet, the Hendo he would be fighting at UFC Fight Night 32 was not quite that guy either. Having failed in two attempts to become a UFC champion at both middleweight and light heavyweight, Hendo was aging, and was coming off 2 losses (albeit close fights) when he faced arguably the most dangerous Vitor Belfort there ever was. Belfort of course, coming off two knockouts now, was more confident than ever, and ready for the challenge of not just securing a title shot against Chris Weidman, but redemption for his loss against Hendo 7 years prior. Henderson told the media he wanted this fight to look largely like their first fight in 2006, but he wanted a finish instead.

Event: UFC Fight Night 32 | November 9, 2013

Record Before Fight: 23-10

Opponent: Dan Henderson

Opponent’s Ranking: 9 (Light Heavyweight – 205 lbs)

Result: Win // KO (Head kick)

Score: 4 points

With Vitor Belfort having morphed into a TRT monster, his stance looked unusually low in the opening moments, perhaps because he was expecting a takedown from Henderson. In the first minute Dan threw 2 noncommittal right hands and landed one but as he closed the distance, ended up just inches away from Vitor, standing squarely, and walked into a left uppercut that reeled him backwards, onto his back. Dan immediately tried to recover full guard as Belfort pounded away. Hendo threatened an armbar briefly and this allowed him to slowly work his way back up, all the while getting mauled, narrowly escaping to his feet. The fact that none of these shots put him out is a testament to his chin and toughness. But it wouldn’t last for long because as soon as he stood straight up, Vitor landed a left high kick that made a vertical thing become horizontal. What goes up must come down.

The Rubber Match

We have arrived at Belfort’s third title shot in the modern era of the UFC, and the window of opportunity for the ultimate glory of becoming a UFC champion is closing fast. There is a caveat here: In February of 2014, NSAC banned the use of TRT for athletes competing within their jurisdiction. This soon spread like fire across the United States commissions, with the UFC enthusiastically in agreeance, vowing to regulate their own international events to ensure fair contests in the absence of a state regulatory body. Vitor’s fight against the UFC Middleweight Champion came a full 15 months following the ban of TRT, so he was no longer using synthetic testosterone. I personally believe Belfort had a massive challenge ahead of him even if he was on TRT, against a guy as good as Chris Weidman, who had the confidence of somebody who had just dismantled the middleweight GOAT twice, and was coming off a pretty dominant win over Lyoto Machida. Vitor was a decent sized underdog against Weidman, showing just how dominant the champ had been. Vitor had some good success early, avoiding a couple of takedowns and getting a collar tie, landing some really hard uppercuts and hooks in close. Chris ate all of it and kept the pressure on, even blocked a head kick (but still kind of ate it), and eventually took Vitor down with perfect timing. After landing thunder on Vitor for a full 45 seconds, the fight was stopped. And with that, Belfort’s title aspirations were finished. I think it’s fair to say that when you match up their skill sets, this was always going to be a bad matchup for Belfort, and his best chance was to land something early. He always struggled against elite wrestlers, and Weidman was very competent on the feet, and was able to get the fight where he wanted it.

Event: UFC Fight Night 77 | November 7, 2015

Record Before Fight: 24-11

Opponent: Dan Henderson

Opponent’s Ranking: 10 (Light Heavyweight – 205 lbs)

Result: Win // KO (punches)

After Vitor and Dan fought for the second time in November of 2013, Dan had gone 2-2 with wins over Shogun and Tim Boetsch, equally as dangerous as he was vulnerable to losing against younger fighters this late into his career. He was 45, and facing Vitor again, who was 7 years younger, and had just beat him 2 years prior. This was seen as a clash of legends without any title or ranking implications, and it saw Vitor as a sizeable favorite, based on the results of their last fight, and most likely the age of Henderson. A lot of fans were picking Vitor but amongst fighters it was more split, with more people thinking Hendo’s power would be the difference. With both possessing ungodly power, both guys looked tentative early on. Two minutes into the first round, Belfort timed Hendo’s footwork as he circled away from Vitor’s left hand, giving him the exact angle he needed to land a left high kick. Hendo tried to duck under it, and block it at the same time, but neither would keep him vertical. This time Belfort didn’t need a lot of follow up shots as Yamasaki stepped in pretty quickly. This would be the last ranked win of his career, as he would go 1-4 in his final five fights, and retire from the sport of MMA after his loss to Lyoto Machida.

Uncrowned King: By The Numbers

Total Ranked Wins: 9

Total Ranked Opponents: 21

Total Fights: 41

Total Points: 35

The Adoptive Son, The Man, The Fighter

There is no way I was doing this series without including Vitor Belfort, one of my all time favorite guys to watch, and one that got me excited about the sport in the mid 2000s. Not many fighters rose to prominence in MMA as quickly as he did, and not many were spoken of as highly, irrelative to their accomplishments in their given sport. Vitor Belfort came into fighting as a prodigy of Carlson Gracie, a title only bestowed upon those deserving of walking in the enormous footprints carved into the foundation of MMA by the Gracie family, and specifically filling the shoes crafted by his “adoptive father” Carlson Gracie. Belfort wasn’t just training under a Gracie, but under one who actively preached and encouraged cross-training, and opened up one of the first MMA academies in the early 1990s. This team, formed in West Hollywood, would be the foundation for some of the legendary teams we hear in MMA: American Top Team, Brazilian Top Team, Nova Uniao, and Black House. The fact that these were all founded by Carlson Gracie black belts shows you the level of skill on those mats during the early days. From this environment Belfort was spawned, and won the Brazilian National Jiu Jitsu championships at the age of 17, in both the heavyweight and absolute divisions. He also won bronze at ADCC in 2001, a year before he won his UFC title. From the beginning he was destined for great things, and great things he achieved, and yet the greatness we witnessed, still left us unfulfilled. Perhaps due to the pressure of being the golden boy in the gym or having 38 cornermen throughout his early career, Belfort didn’t quite live up to the expectations those early days set up for him. Although we saw Vitor struggle with Randy at UFC 15, we all thought Belfort would be all the better for it, and to be fair, we were right. We just weren’t right to the extent that we thought we would be. It elevated his game but it made him a different fighter, as he no longer had the confidence of “Victor Gracie”. Not due to any lack of effort or skill, once he lost that aura, he didn’t believe in himself the way he kept believing in his power. This was evident in the way he often fought, looking to take his opponents out in the first round, with his chances of winning diminishing as the rounds wore on. He proved he was durable and tough in his fights against Chuck Liddell, Overeem and Tito, but that same toughness didn’t present itself ubiquitously throughout the years, as well as the desire to win. I think Vitor Belfort will be remembered for his destructive power and explosiveness, willingness to fight the best, and longevity in a sport full of brain damage and bankruptcy. I can’t stress just how much pressure was on Vitor, with some expressing he could go on to be one of the greats in the sport, and they weren’t necessarily wrong, just not quite right. Not to mention he had to uphold the reputation of the mighty Gracies, having his every move gazed upon by wandering eyes. Ultimately I think he was in his absolute peak mentally and physically going into the Anderson Silva fight. To me, I saw a calmness and confidence that I had yet to see from him. The confidence of 1997 Belfort with the skills and experience of the man who knocked out Rich Franklin and Matt Lindland. I will never forget that front kick, as my soul briefly left my body that night, and I believe it’s the night Belfort’s title dreams ended, regardless of the last two times he fought for a belt. Regardless, he fought the best fighters of three generations, beat a lot of them, and knocked some of them seemingly dead. He gave us countless transformations, and some of the most memorable knockouts in modern MMA history. Immortalized you are, Phenom.

References

- Tapology. “Vitor Belfort (‘The Phenom’): MMA Fighter Page.” Tapology, www.tapology.com/fightcenter/fighters/vitor-belfort-the-phenom. Accessed 14 Apr. 2025.

- ShinSplints. “TRT Not Winning Fights in UFC.” Bloody Elbow, 30 June 2013, bloodyelbow.com/2013/06/30/trt-tesosterone-replacement-losing-record-ufc/.

- Nswix. “Vitor Belfort.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 7 Apr. 2025, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vitor_Belfort.

*All fight footage used to write this article is copyrighted and owned by Endeavor Group Holdings Inc.